Leon M. Lederman was born on July 15, 1922, to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents in New York City. His father, who operated a hand laundry, revered learning. Lederman graduated from the City College of New York with a degree in chemistry in 1943, although by that point, he had developed an interest in physics and become friends with a group of physicists. He served three years with the United States Army in World War II and then returned to Columbia University in New York to pursue his Ph.D. in particle physics, which he received in 1951. During graduate school, Lederman joined the Columbia physics department in constructing a 385-MeV synchrocyclotron at Nevis Lab at Irvington-on-the Hudson, New York. He remained a member of that collaboration for 28 years and eventually served as director of Nevis labs from 1961 to 1979.

In 1956, while working as part of a Columbia team at Brookhaven National Laboratory, Lederman discovered the long-lived neutral K meson. In 1962, Lederman, along with colleagues Jack Steinberger and Melvin Schwartz, produced a beam of neutrinos using a high-energy accelerator. They discovered that sometimes, instead of producing an electron, a muon is produced, showing the existence of a new type of neutrino, the muon neutrino. That discovery eventually earned them the 1988 Nobel Prize in physics.

Through Lederman’s early award-winning work, he rose to prominence as a researcher and began to influence science policy. In the early 1960s, he proposed the idea for the National Accelerator Laboratory, which eventually became Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab). He worked with laboratory founder Robert R. Wilson to establish a community of users, credentialed individuals from around the world who could use the facilities and join experimental collaborations.

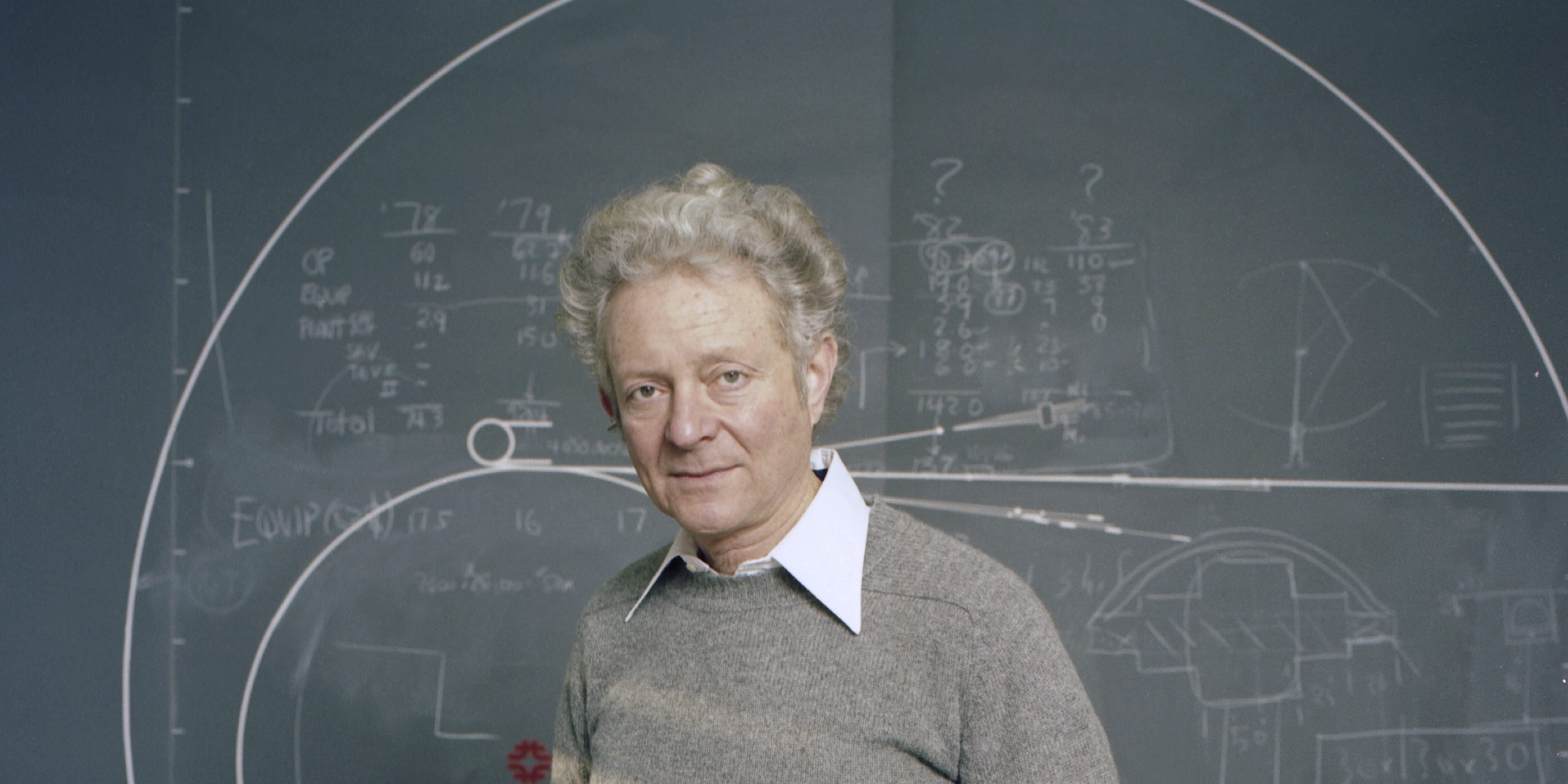

Lederman began his tenure as Fermilab director in 1978. As a charismatic leader and a respected researcher, Lederman unified the Fermilab staff and rallied the U.S. particle physics community around the idea of building a proton-antiproton collider. Originally called the energy doubler, the particle accelerator eventually became the Tevatron, the world’s highest-energy particle collider from 1983 until 2010.

With a career that spanned more than 60 years, Lederman became one of the most important figures in the history of particle physics. He was responsible for several breakthrough discoveries, uncovering new particles that elevated our understanding of the fundamental universe. But perhaps his most critical achievements were his influence on the field and his efforts to improve science education.

Lederman had a significant impact on the next generation of scientists. It was during his years at Columbia, an institution that required students to teach, that Lederman developed a passion for science education and outreach, which became a theme throughout his career. Between 1951 and 1978 he mentored 50 Ph.D. students. He liked to joke about their success, saying that not a single one was in jail.

As director of Fermilab, Lederman established the ongoing biannual Saturday Morning Physics program. For decades, Chicagoland students have taken advantage of this opportunity to expand their understanding of particle physics with expert guidance from leading scientists.

During his career, Lederman received some of the highest national and international awards and honors given to scientists. These include the 1965 National Medal of Science, the 1972 Elliot Creeson Medal from the Franklin Institute, the Wolf Prize in 1982, and the Nobel Prize in 1988. He received the Enrico Fermi Award in 1992 for his career contributions to science, technology, and medicine related to nuclear energy and the science and technology of energy, and was given the Vannevar Bush Award in 2012 for exceptional lifelong leaders in science and technology.